Pre-Fight Ceremony

Lethwei, beyond its distinctive fighting style, would not be what it is without its vibrant and charismatic traditions. One such tradition is the opening ceremony, held at the start of every match. Rooted in traditional customs, this ritual invokes good fortune for both fighters.

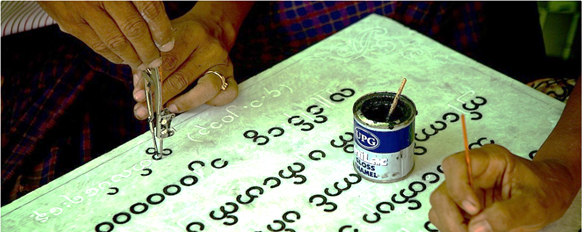

During the ceremony, referees and match organizers take the lead, arranging an array of symbolic offerings—coconuts, bananas, pineapples, betel leaves, red grass accompanied by old coins, lit candles, and incense sticks placed on large dishes. As the orchestra plays a special melody for the occasion, the referees and organizers move around the ring’s corners in a ceremonial procession. Once the ritual is complete, the fight begins.

The content displayed on this webpage is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to be replicated, reenacted, or attempted by anyone viewing the video. Viewer discretion is advised.

This webpage includes a small clip from a video for educational purposes under the fair use doctrine (17 U.S.C. § 107). The use of this clip is intended to enhance learning by providing commentary, criticism, research, and analysis. This use is non-commercial and transformative, adding educational value beyond the original content. We respect the rights of the original copyright holder and do not claim ownership of the video. If you are the rights holder and have concerns about this use, please contact us, and we will address any issues promptly.